Pay-to-work wildlife conservation internships—programs requiring participants to pay fees for field placement—are rarely justified on economic grounds alone, since paid interns earn 1.15 to 1.4 times higher starting salaries and receive nearly 50% more job offers than their unpaid counterparts. These arrangements may serve narrow career purposes when free or paid alternatives can’t provide equivalent access to remote field sites, rare species work, or geographic regions essential to specific research goals, though candidates should carefully weigh the tangible benefits against both direct costs and lost wages. The sections ahead explore how to evaluate whether a particular program merits the investment.

Key Takeaways

- Pay-to-work programs may be justified when they include structured training, credentials, and supervised mentorship unavailable through traditional employment pathways.

- International placements in remote locations with limited budgets can justify fees if they cover accommodation, meals, safety equipment, and field logistics.

- Programs offering unique access to specialized research or rare species conservation may warrant fees when alternative paid opportunities don’t exist.

- Fees are harder to justify when participants perform routine work that primarily benefits the organization without meaningful educational components or credentials.

- Paid internships consistently yield better career outcomes—higher starting salaries and more job offers—making fee-based programs difficult to justify economically.

What Are Pay-to-Work Wildlife Conservation Internships?

How exactly do pay-to-work wildlife conservation internships operate, and what distinguishes them from the traditional employment arrangements most people expect?

These programs require participants to pay fees—sometimes substantial—to organizations in exchange for placement, training, or access to conservation work, reversing the compensation flow entirely.

Unlike conventional paid internships where employers compensate interns for their contributions, pay-to-work models position the experience itself as the primary value proposition, marketed as educational investments emphasizing skill development and networking opportunities.

Historical origins trace to funding limitations in conservation sectors, where high demand for positions and organizational budget constraints created conditions favoring fee-based structures.

Program accreditation varies widely, with some internships offering formal credentials while others provide only experiential learning without standardized oversight or quality guarantees.

Conversely, some organizations like Carolina Waterfowl Rescue offer modest stipends upon completion, providing $250 for part-time or $500 for full-time wildlife rehabilitation interns who successfully finish their programs.

How Pay-to-Work Programs Differ From Paid Internships

While paid internships and pay-to-work wildlife conservation programs both promise career-building opportunities, they operate on fundamentally opposite financial models, creating starkly different experiences for participants.

Paid interns receive hourly wages—averaging $15.67 to $19.51 depending on experience—and enjoy protection under labor laws that mandate minimum wage, overtime pay, and regulated working conditions.

In contrast, pay-to-work programs require participants to pay upfront fees, effectively reversing the compensation flow while often sidestepping employment regulations by classifying arrangements as educational programs rather than jobs.

This Legal Classification distinction affects Insurance Coverage, workplace protections, and employer obligations.

Paid interns contribute substantive work that validates their financial compensation, whereas fee-paying participants engage in tasks that primarily benefit conservation organizations, raising questions about who truly gains from these arrangements. Monetary compensation fosters respect and professionalism in traditional internship settings, a dynamic entirely absent when participants must pay for the privilege of contributing their labor.

Typical Fee Ranges: What Programs Actually Charge

Pay-to-work wildlife conservation programs charge fees that span an enormous range, from roughly $175 per week at smaller international organizations to nearly $10,000 for prestigious summer experiences, a pricing spectrum that reflects differences in location, organizational reputation, and what’s bundled into the cost.

Program bundling—the practice of combining accommodation, meals, training, and field support into one fee—explains much of this variation, with all-inclusive packages like Kanahau’s $350 weekly rate including airport pickup and supervision, while bare-bones options cover only coordination costs.

Seasonal pricing appears in National Geographic’s summer programs ($7,990–$9,590), which concentrate during peak June-to-August months when students can participate.

University researchers often receive modest discounts, paying $300 weekly compared to standard intern rates, though week-long intensive programs like Smithsonian-Mason’s $2,300 offering represent another pricing model entirely.

Extended stays frequently unlock reduced weekly rates, with Kanahau dropping from $350 to $250 per week after the initial three-week minimum period.

What’s Usually Included in Pay-to-Work Internship Fees

Understanding what these programs charge matters less than understanding what participants receive for their money, since the value proposition depends entirely on whether fees translate into meaningful support or simply administrative overhead.

Most pay-to-work wildlife conservation internships offer surprisingly limited inclusions compared to traditional employer-funded positions, and participants should examine fee breakdowns carefully before committing.

Typical inclusions across programs include:

- Basic dormitory-style housing or modest housing allowances

- Limited meal plans or kitchen access rather than full catering

- Essential safety equipment and field gear rentals

- Supervised training sessions with experienced conservation staff

- Transportation to field sites, though rarely airport transfers

Programs rarely provide welcome kits, campus tours, or thorough onboarding experiences that justify substantial fees, making transparency about actual costs essential for prospective participants evaluating whether program value aligns with financial investment.

In contrast, competitive paid internships like those at the Center for Conservation Innovation typically cover local transportation costs up to $10 per day when interns work in office, demonstrating how employer-funded positions absorb operational expenses rather than passing them to participants.

Choosing a reputable organization like Global Work & Travel ensures that your contribution truly supports ethical and sustainable projects.

They provide comprehensive support — including visa assistance, pre-departure guidance, 24/7 in-country and emergency help, and a dedicated trip coordinator. Every project is carefully vetted for animal welfare and conservation integrity, ensuring placements are in sanctuaries, rescue, or rehabilitation centers rather than exploitative settings.

You’ll also receive structured mentorship, feedback, and official certificates and recommendation letters from host organizations — valuable credentials for your career or academic path.

Plus, you’ll get $100 off automatically, and by adding the additional code ELI100 at checkout, you can save an extra $100, for a total of $200 off your Global Work & Travel wildlife internship adventure.

Ready to volunteer or intern abroad? Enter code ELI100 at checkout and get $100 OFF any internship or volunteer project worldwide.

Explore ProjectsHidden Expenses Beyond the Advertised Program Fee

Beyond the headline program fee that conservation organizations advertise on their websites, participants discover a cascade of additional expenses that collectively dwarf the initial payment, transforming what seemed like a manageable financial commitment into a burden that stretches across months or even years.

International flights, visa applications, and mandatory health insurance—sometimes $160 for just three months—appear immediately, while equipment purchases like tents and specialized gear can exceed $1,600.

Field station surcharges, meals in remote areas, and pet care arrangements back home add unexpected layers.

Even banking fees for international transfers chip away at shrinking budgets. The true cost emerges gradually: lost wages from unpaid positions, lodging during program gaps, and fuel for site visits, creating financial pressures that extend far beyond the advertised price.

Graduate students frequently absorb travel expenses by redirecting portions of their stipends toward fieldwork costs that grants fail to cover, essentially subsidizing research opportunities from funds intended for their basic living expenses.

Calculate What Your Unpaid Labor Is Actually Worth Per Hour

Once the full scope of expenses becomes clear, participants face another calculation altogether: the monetary value they’ve forfeited by working without wages, a figure that often exceeds every program fee and travel cost combined. This opportunity cost—potential earnings sacrificed while working unpaid—requires honest task breakdown, examining each responsibility as if it were compensated employment. Wildlife conservation interns often perform skilled labor that deserves skill monetization based on established market rates.

Consider these calculation steps:

- Track total hours spent on fieldwork, data collection, and administrative tasks throughout the program

- Research typical hourly wages for comparable paid internships in environmental fields ($10.10 to $34.13 nationally)

- Multiply total hours by a conservative wage estimate to determine forgone income

- Add this opportunity cost to direct program expenses for complete financial impact

- Compare the total against tangible career benefits gained

Understanding how your unpaid work compares to paid employee standards helps clarify whether the experience justifies the financial sacrifice. Paid interns receive documentation showing their earnings and tax withholdings, creating transparent records of their labor’s worth—a stark contrast to pay-to-work arrangements where participants subsidize their own training while performing tasks that might otherwise require compensated staff.

When Paying for an Internship Makes Financial Sense

While the previous calculations reveal the true cost of unpaid conservation work, the data on paid internships tells a different story entirely, one where investing money into an experience might actually contradict basic financial logic.

Paid interns earn 1.15 to 1.4 times more in starting salaries and receive nearly 50 percent more job offers than their unpaid counterparts, establishing market signaling—the way compensation communicates value to future employers.

The $3,096 annual wage increase one year post-graduation, combined with compounding career-long earnings, suggests paying for internships carries a risk premium, the extra cost participants absorb for uncertain returns.

When students finance their own positions, they’re effectively gambling against proven outcomes, betting on connections that research indicates provide minimal immediate financial benefit compared to compensated experience.

This wage advantage persists after controlling for field of study, gender, and race/ethnicity, demonstrating that the benefits of paid internships transcend individual career paths and demographic factors.

Ready to volunteer or intern abroad? Enter code ELI100 at checkout and get $100 OFF any internship or volunteer project worldwide.

Explore ProjectsWhen Free or Paid Alternatives Exist for the Same Experience

The financial argument against pay-to-work internships becomes even more compelling when nearly identical experiences—same locations, similar conservation tasks, comparable durations—exist without participant fees or, better yet, with actual compensation.

Before committing thousands to a wildlife program, aspiring conservationists should explore alternatives demonstrating community reciprocity—organizations that value interns enough to cover their costs or provide wages:

- SFS internships include stipends, on-site housing, insurance, and program travel for typically one year

- Nature Conservancy’s GLOBE program mirrors three-month durations of fee-based experiences without charges

- Wild Sun Rescue Center offers twelve-week wildlife biology internships with training and certificates, fees unmentioned

- Malaysian programs charge only minimal administrative costs for accommodation and meals

- Virtual alternatives through Conservation Careers webinars outline systematic approaches to finding no-cost opportunities matching career goals

Competition for quality positions remains intense, with some internships attracting hundreds of applications for single openings, yet this shouldn’t deter candidates from pursuing legitimate no-fee opportunities over expensive alternatives.

How to Evaluate Whether a Fee-Based Internship Is Worth It

Before committing to a pay-to-work wildlife internship, aspiring conservationists should approach the decision with the same analytical rigor they’d apply to evaluating a college program or major purchase, recognizing that financial investment alone doesn’t guarantee career advancement or meaningful learning.

A thorough contract review should itemize all fees—registration costs, program charges, and ancillary expenses—while verifying whether paid alternatives exist in the same conservation field that could offset these outlays.

Prospective interns must assess whether the experience provides measurable skill development in critical thinking and problem-solving, documented learning outcomes connected to degree requirements, and qualified supervisor oversight with regular feedback sessions.

The decision’s impact on mental health matters too: excessive financial strain combined with unpaid work can undermine the educational value that justifies the investment initially.

Research shows that 46% of students cannot participate in internships when they are unpaid, highlighting how fee-based positions create barriers for many aspiring wildlife professionals who need to earn income during their training periods.

Red Flags That Signal an Exploitative Pay-to-Work Program

Knowing which factors matter when evaluating a program sets the stage for recognizing warning signs that indicate an organization might prioritize profits over participants’ professional growth.

Contract Ambiguity—vagueness about what participants receive in exchange for their fees—often masks exploitative Power Dynamics where organizations hold all leverage while volunteers subsidize operations without clear benefits.

Watch for these red flags:

- Vague fee breakdowns that don’t specify how much goes toward training, meals, lodging, or actual conservation work

- Overpromised career outcomes like employer recognition or job placement with no concrete post-program support

- Minimal structure where placements feel like conveyor belts offering basic tasks rather than skill development

- Hidden costs that create far less return than expected on time and money investments

- Exclusionary requirements demanding full-time availability, favoring only those with existing financial resources

- Unclear terminology that conflates volunteering with internships or training, obscuring the experience’s true purpose and what you should expect

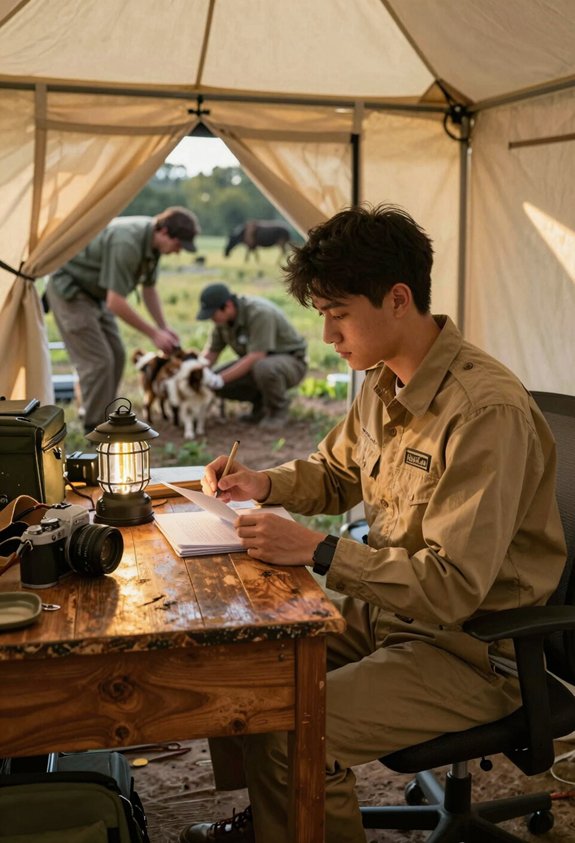

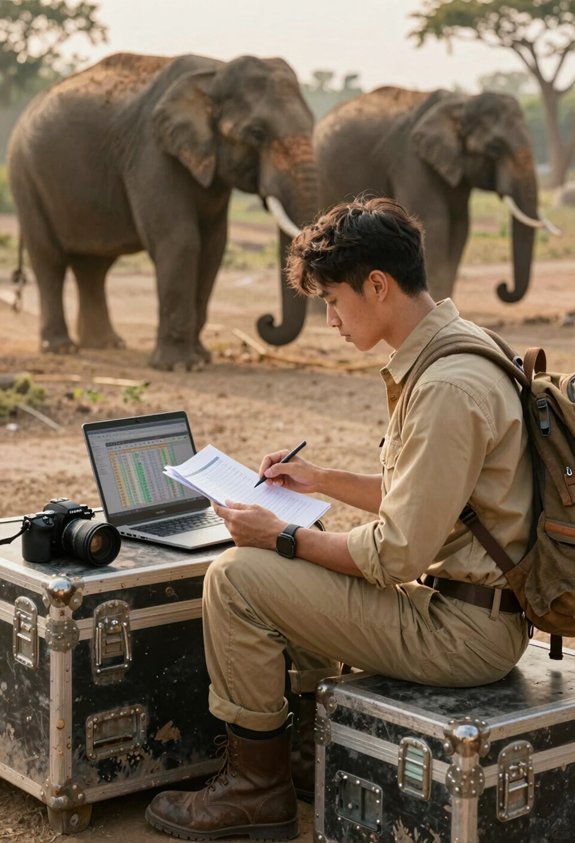

Comparing Skill Development in Paid vs. Fee-Based Programs

When aspiring conservationists weigh their options, understanding how paid internships and fee-based programs differ in skill-building becomes essential to making choices that align with career goals rather than just passion alone.

Paid positions typically emphasize employment progression—offering salary, mentorship, and structured training that builds toward long-term career advancement.

Fee-based programs, lasting four or more weeks, focus intensively on skill development through hands-on practice in GPS mapping, camera traps, and biodiversity surveys. Assessment metrics—the standards used to measure learning outcomes—reveal that graduates from longer programs often produce peer-reviewed reports and publications. Skill transferability, meaning how well abilities apply across different conservation contexts, increases substantially when participants manage projects independently, develop scientific writing capabilities, and receive LinkedIn endorsements from experienced supervisors who recognize their growing expertise.

Programs offering internationally recognized qualifications provide credentials that enhance credibility when applying to conservation positions worldwide.

Do Fee-Based Internships Actually Lead to Conservation Jobs?

Whether fee-based internships translate into actual employment remains the question that haunts prospective conservationists scrolling through program websites.

Checkbooks in hand and dreams of fieldwork filling their minds.

The troubling reality is that specific outcome data comparing fee-based programs to paid internships simply doesn’t exist in available research.

This leaves applicants to navigate this decision effectively blind.

What we do know about conservation employment suggests caution:

- Conservation positions receive 250 to 500+ applications on average

- Job seekers apply to roughly 39 positions yearly, facing rejection rates exceeding 90%

- Acceptance rates for competitive programs hover around 6%

- Brand recognition from established organizations creates networking advantages

- Perceived legitimacy matters when employers review hundreds of applications

Without concrete employment data, fee-based programs remain an expensive gamble in an already brutal job market.

Meanwhile, some organizations offer stipend-based wildlife internships that provide modest compensation upon successful completion, though these positions remain highly competitive with minimal experience requirements.

What Top Conservation Organizations Pay Interns

The stark contrast between paying thousands for an internship and earning actual compensation becomes clearer when examining what legitimate conservation organizations actually offer their interns, figures that reveal both the baseline standards of ethical programs and the real financial possibilities within this competitive field.

Geographic variance plays a significant role, with California positions reaching $23-$25 hourly while Midwest opportunities start at $15, reflecting regional cost-of-living differences that affect purchasing power. Weekly stipends range from modest $100 amounts to substantial $800 packages for full-time commitments, while nonprofit rankings show established programs like USFWS providing robust support—$620 weekly allowances plus housing, travel funds, and mentorship.

Organizations committed to accessibility increasingly offer living allowances, healthcare, and childcare rather than charging participation fees, demonstrating that ethical conservation work compensates contributors rather than extracting payment from them.

Programs like the Conservation Nation Chrysalis Fund support partnerships with organizations including Detroit Hives, Galveston Bay Foundation, and Inland Seas Education Association to expand internship opportunities in the field.

Why Do Some Organizations Charge Internship Fees?

Conservation organizations find themselves caught between mission and money, operating within budgets so constrained that protecting habitats and wildlife consistently takes precedence over administrative costs like intern compensation.

When salaries aren’t feasible, some organizations charge participant fees to cover essential operational expenses:

- Accommodation, meals, and transportation throughout the internship period

- Insurance coverage, orientation services, and logistical coordination for international placements

- Field equipment, training materials, and administrative infrastructure necessary for program operation

- Staffing costs for supervision and mentorship that guarantee meaningful learning experiences

- Program sustainability that allows organizations to maintain internships without institutional salary budgets

These fee structures, while addressing organizational constraints and market positioning among volunteer tourism options, raise serious questions about legal compliance and workforce equity that conservation can’t ignore. The resulting financial barriers effectively exclude candidates without parental support or independent means, narrowing the talent pool to those with existing economic privilege.

Ready to volunteer or intern abroad? Enter code ELI100 at checkout and get $100 OFF any internship or volunteer project worldwide.

Explore ProjectsWhere Pay-to-Work Conservation Internships Are Most Common

While fee-based programs exist within the conservation sector, they don’t represent the dominant model in wildlife internship opportunities, particularly within the United States where government agencies and established nonprofits have increasingly moved toward compensated positions over the past decade.

Pay-to-work arrangements appear most frequently in international settings—especially Island Reserves and Private Reserves in locations like Mauritius, where geographic isolation and specialized conservation needs create different funding structures.

These programs often require participants to contribute financially toward project operations, housing, and logistical support.

In contrast, domestic opportunities through agencies like the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Park Service, and organizations such as the Wildlife Conservation Society now primarily offer stipends, hourly wages, or extensive support packages that eliminate financial barriers for students. Organizations like the Wildlife Conservation Society typically pay interns around $22.52 per hour, which is above the national average for similar positions.

How Some Organizations Fund Internships Without Charging Fees

Rather than asking students to pay for the privilege of gaining experience, numerous conservation organizations have developed creative funding structures that allow them to offer stipends, housing support, and other financial assistance to interns.

These models demonstrate that conservation work can remain accessible without creating financial barriers for participants.

Organizations secure funding through several approaches:

- Federal partnerships where agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Forest Service provide complete program funding

- Grant programs such as IMLS awards, which provided Wildlife Conservation Society with $250,000 for supervisor training

- Corporate Sponsorships from businesses committed to environmental stewardship

- Endowment Funding that generates sustained income for internship programs

- Cost-share arrangements combining institutional resources with external contributions

These strategies enable organizations to provide meaningful compensation while maintaining program quality.

Wisconsin’s Natural Resources Foundation offers interns a $6,800 stipend for their 10-week summer conservation program, demonstrating how state-level organizations can support undergraduate participants without charging fees.

How Stipended Programs Provide a Middle-Ground Solution

Between the extremes of unpaid opportunities that exclude students without financial safety nets and pay-to-work programs that create immediate debt, stipended internships offer compensation that acknowledges the value of interns’ contributions while remaining financially sustainable for host organizations.

WWF’s $3,410 monthly stipend demonstrates this sustainability balance, providing meaningful support without overwhelming nonprofit budgets.

UK conservation roles set wages at £7.83–£9.75 hourly, ensuring basic financial dignity while maintaining program viability.

USFWS partnerships illustrate creative funding—combining housing, food allowances, and biweekly payments through collaborations with educational institutions and Friends groups.

These models promote community integration by enabling diverse participants, including those from underrepresented backgrounds, to engage in hands-on conservation work.

Stipends represent practical compromise: they remove prohibitive barriers while preserving organizations’ capacity to train future conservation professionals effectively.

Organizations like WWF place interns within active conservation teams working on projects ranging from wildlife protection to climate policy, ensuring contributions extend beyond administrative duties.

The True Cost of Paying to Volunteer in Wildlife Conservation

Programs that charge participants for wildlife conservation work create a financial barrier that operates in reverse of traditional employment, requiring aspiring conservationists to pay hundreds or thousands of dollars for the privilege of contributing their labor.

The emotional toll of this arrangement can weigh heavily on those passionate about protecting wildlife yet financially constrained, while the environmental footprint of international travel adds ethical complexity.

Consider what these fees actually cover:

- Hoja Nueva’s Amazon internships charge $515 per week or $6,300 for six months

- One Health programs require $500 weekly regardless of duration

- Costs include lodging at research centers with expert teams

- Participants work alongside jaguars, pumas, and ocelots at high-end facilities

- Fees support cash-strapped organizations that couldn’t otherwise operate

These programs ultimately funnel resources into conservation work that mightn’t exist otherwise.

In contrast, the National Park Service offers paid conservation internships through programs like Fish and Feathers, which provides a $640 weekly stipend plus travel and housing for eligible participants aged 15 to 30.

3 Career Scenarios Where Paying for Experience Makes Sense

While traditional employment models expect employers to pay workers for their time and effort, certain career scenarios flip this arrangement in ways that can actually advance a person’s professional trajectory, particularly when financial resources allow and strategic career benefits outweigh immediate costs.

Career pivoting—shifting from one professional field to another—sometimes requires investing in experiences that demonstrate commitment and build foundational skills.

Individuals with higher risk tolerance, meaning the ability to absorb financial uncertainty without jeopardizing essential needs, can leverage pay-to-work internships as strategic tools.

When someone possesses savings or family support, paying for specialized training in wildlife conservation can test career fit before committing to graduate programs.

These arrangements make sense when they provide mentorship opportunities, hands-on skills, and networking connections unavailable through traditional routes, effectively functioning as accelerated professional development rather than exploitative labor practices.

Pay-to-work experiences offer low-risk career exploration by allowing professionals to test whether wildlife conservation aligns with their interests and abilities without the pressure of long-term commitments.

Who Really Benefits When You Pay to Work?

When examining pay-to-work arrangements in wildlife conservation, the central question becomes not whether anyone benefits, but rather who captures the value these arrangements create—and at whose expense.

The evidence from traditional internships reveals systematic patterns worth considering:

- Women, people of color, and first-generation students face substantially reduced access to paid opportunities

- Alumni networks and employer reputation grow stronger through free labor rather than through investment in participants

- When organizations shift to paid models, demographic participation transforms dramatically—as the Democratic National Committee discovered when diversity jumped from 18% to 42%

- Paid participants receive 72% job offer rates compared to 43% for unpaid counterparts

- Starting salary advantages compound over time, either closing or widening existing economic gaps

These patterns suggest pay-to-work models primarily benefit organizations seeking skilled labor without compensation costs.

Graduates who completed paid internships can earn up to 12% higher salaries than their peers without such experience, suggesting that compensation during early career development has lasting financial implications.

Why Only Wealthy Students Can Afford Pay-to-Work Internships

The organizations capturing value from free labor aren’t the only ones shaped by economic forces—the students who can access these opportunities face financial filters that begin long before they submit applications.

Wealthy undergraduates can afford $3,595+ program fees plus living expenses during unpaid periods, while low-income students must choose between career development and immediate income.

This creates a tiered system where cultural capital—the knowledge, behaviors, and credentials that signal belonging in professional spaces—accumulates among those who can afford repeated internships.

First-generation college students lack family safety nets to support unpaid work, and social expectations within conservation normalize this arrangement: prestigious organizations operate on assumptions that serious candidates possess financial resources to work without compensation, effectively gatekeeping who enters the profession.

Programs marketed toward students and recent graduates promise resume enhancement and international experience, yet the minimum four-week commitment further excludes those who cannot afford extended periods without earned income.

How Pay-to-Work Models Reduce Diversity in Conservation

Financial barriers don’t affect all students equally, and this uneven impact directly shapes who can enter conservation careers.

Research shows that minority students required 24% more monthly compensation than white students to accept field positions, while accumulated wealth disparities made unpaid work financially impossible for many talented candidates from underrepresented communities.

This creates what researchers call Pipeline Attrition—the gradual loss of diverse candidates at each career stage:

- Students whose financial needs exceed available stipends face immediate exclusion from necessary field experiences

- Male employees of color start at lower grades and experience higher termination rates

- Women’s representation in federal agencies actually declined during diversity initiative periods

- Cultural Exclusion through incompatible schedules and noninclusive environments compounds financial barriers

- One-fifth of organizations still offer unpaid positions despite documented diversity consequences

Organizations that commit to fully paid internships can more effectively recruit from underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, veterans, and people with disabilities.

How Your Financial Situation Should Guide Your Decision

Before accepting any conservation internship that requires payment or offers minimal compensation, prospective participants need to conduct what financial advisors call a cost-benefit analysis—a systematic comparison of what they’ll spend against what they’ll gain, measured not just in immediate dollars but in long-term career value.

This evaluation starts with honest assessment of current financial stability: whether an emergency fund exists to cover unexpected expenses during the internship period, and whether family obligations—such as supporting children or contributing to household income—make temporary earnings loss manageable. Individuals with existing savings face fundamentally different constraints than those dependent on continuous paychecks.

Internships charging $1,850 monthly demand not just that amount but also calculations of foregone wages, travel costs, and whether provided housing truly reduces expenses sufficiently to justify participation. Students should investigate whether their academic institution offers experiential learning funds that can offset internship costs, particularly for opportunities in wildlife, fish, or conservation organizations that might otherwise be financially inaccessible.

Negotiating Fee Reductions or Payment Plans With Programs

Once someone has determined through careful calculation that they can’t afford a pay-to-work internship at its posted price, the natural next step involves asking whether the hosting organization offers any flexibility—whether through partial fee reductions, payment plans that spread costs across multiple months, or case-by-case financial accommodations for candidates whose qualifications match program needs but whose bank accounts don’t.

Relationship building with program coordinators creates space for honest conversations about financial barriers, while timing strategy matters because applying early signals genuine interest that may motivate coordinators to explore options.

Consider these approaches:

- Request specific payment schedules that align with personal income patterns

- Ask whether partial scholarships exist for underrepresented applicants

- Inquire about reduced fees in exchange for extended volunteer commitments

- Propose budgets showing exactly what you can contribute

- Follow up respectfully if initial responses seem uncertain

Some organizations that operate SCA national recruiting networks pre-screen candidates and submit them to partners, which can streamline the application process and potentially open doors to discussing financial arrangements with the ultimate placement site.

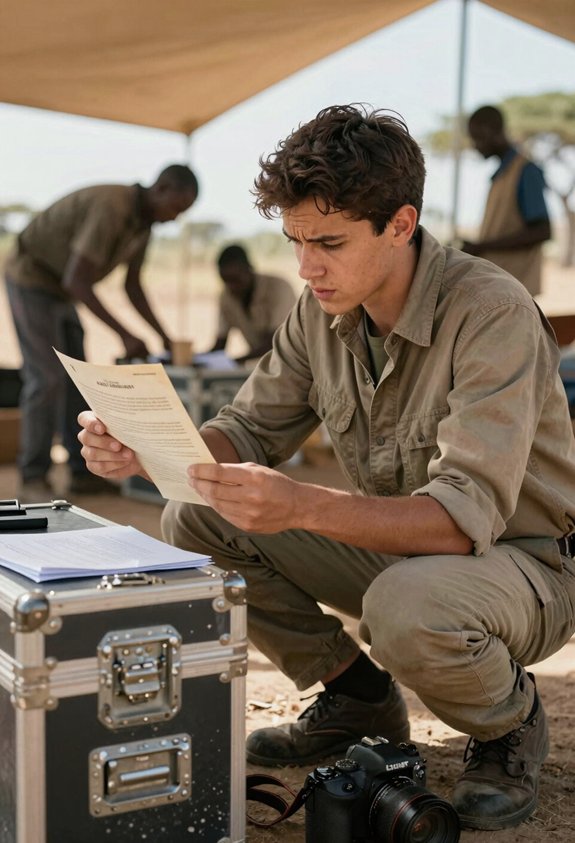

What to Ask Before Committing to a Pay-to-Work Internship

How can someone distinguish between a pay-to-work internship that genuinely advances career goals and one that merely extracts fees while offering little substance—a question that becomes urgent once negotiations conclude and commitment looms?

Before signing contracts, prospective interns should request detailed descriptions of daily duties, asking whether tasks align with stated learning objectives rather than serving as unpaid labor disguised as education.

They must confirm that hosting agencies provide written evaluations and letters verifying completed work, since these documents prove value to future employers.

Inquiring about Cultural Fit—the alignment between personal values and organizational mission—helps promote meaningful engagement throughout the tenure.

Understanding Workload Limits, including whether programs require manageable hours like the standard 135 minimum or demand excessive time, protects against burnout while maintaining academic credit eligibility.

Candidates should verify that internships include mentorship by experienced staff, as structured guidance transforms routine tasks into genuine professional development opportunities.

Tax Breaks and Educational Credits for Internship Fees

While pay-to-work wildlife conservation internships rarely qualify for direct tax deductions as educational expenses,

participants may discover financial relief through related pathways that depend on program structure and individual circumstances.

Consider these potential avenues:

- Educational credits: If the internship connects to degree requirements at an accredited institution, participants might access education tax credits, though tax reciprocity—the mutual recognition of tax benefits across state lines—varies by location

- Charitable donations: Fees paid directly to qualifying 501(c)(3) organizations could be partially tax-deductible up to 60% of adjusted gross income

- State-specific benefits: Some states offer credit portability, allowing educational benefits to transfer between programs or institutions

- Conservation easements: Unlikely for interns but worth understanding for future land stewardship

- Professional development deductions: Career-related expenses may qualify under specific employment situations

- Field-specific eligibility: Programs targeting professionals or students in Animal Sciences or related fields may strengthen claims for education-related tax benefits

Funding Sources to Help Cover Pay-to-Work Internship Costs

Beyond managing tax considerations, aspiring wildlife conservationists can explore a diverse landscape of funding sources that directly offset or eliminate internship costs altogether.

Private foundations like the American Wildlife Conservation Foundation award up to $2,000 for supplies or travel—proposals are due February 1 or August 1.

The Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation supports summer internships for graduate students, while federal grants through grants.gov fund environmental work with agencies like the Forest Service.

Students shouldn’t overlook employer sponsorship, where conservation organizations sometimes cover program fees in exchange for committed service.

Crowdfunding campaigns represent another viable path, allowing interns to share their conservation mission with family, friends, and online communities who value wildlife protection.

The National Sea Grant Program sponsors marine projects through state programs, creating additional avenues for financial support.

The Student Conservation Association partners with federal agencies to offer living stipends, housing, and relocation funding for short-term conservation positions.

Scholarships and Grants Specifically for Conservation Interns

Dedicated scholarship and grant programs exist specifically to support conservation interns, addressing the financial barriers that prevent talented students from gaining essential field experience.

These opportunities vary in award criteria, from emphasizing underrepresented backgrounds to prioritizing specific research locations, though selection transparency differs across programs.

Notable funding sources include:

- PTES Wildlife Conservation Internship Awards fund UK-focused projects up to six months, processing applications within six weeks year-round

- Lloyd W. Swift Endowment Fund provides UC Davis students up to $7,500 per career for internships, field courses, and research expenses

- Sacramento-Shasta Chapter grants offer $200–$2,500 for California/Nevada opportunities, targeting first-generation students and underrepresented groups

- Conservation Nation programs support early-career individuals lacking privilege through internship funding and professional development

- WCS Research Fellowship provides small grants for fieldwork on threatened species across global regions

The PTES program requires joint applications between students and host organizations, ensuring both parties commit to the mentorship-based experience before funding approval.

Your Pre-Application Checklist: 12 Questions to Ask Before Paying

How can prospective interns distinguish between legitimate professional development opportunities and programs that exploit their enthusiasm for conservation work?

Before committing funds, applicants should verify host transparency—whether organizations openly share costs, timelines, and deliverables like presentations or reports.

They must confirm safety protocols exist for fieldwork conditions, including procedures for hot weather, biting insects, or carrying heavy loads up to 50 pounds.

Questions about supervision ratios, emergency contacts, and insurance coverage reveal program integrity.

Applicants should ask if hosts provide letters of recommendation, transcripts of completed hours, or professional references after the internship ends.

Understanding whether the program offers structured mentorship, rather than merely unpaid labor, helps distinguish developmental experiences from exploitative arrangements that primarily benefit the host organization.

Programs using standardized application forms can signal organizational professionalism, as they demonstrate consistent data collection processes and systematic candidate evaluation rather than ad hoc recruitment practices.

Ready to volunteer or intern abroad? Enter code ELI100 at checkout and get $100 OFF any internship or volunteer project worldwide.

Explore ProjectsIf you’re exploring hands-on experience in ecology or wildlife biology, don’t miss my complete guide to wildlife conservation internships with global work and travel, where I break down what’s worth your time, money, and long-term career goals.

References

- https://cnhp.colostate.edu/internship/

- https://conservancy.org/about/work-here/

- https://toucanrescueranch.org/services/release-site-wildlife-care-internship/

- https://www.conservation-careers.com/top-conservation-internships/

- https://www.seaturtlehospital.org/rehabilitation-conservation-education-internship.html

- https://sandiegozoowildlifealliance.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/2025 Wildlife Care Summer Internship (rev2411v3).pdf

- https://thesca.org/internship-benefits-18-yrs

- https://animalparknc.org/internships/

- https://wildhub.community/discussions/is-paying-for-a-conservation-internship-worth-it

- https://www.conservationjobboard.com/job-listing-wildlife-rehabilitation-and-animal-care-springsummer-intern-indian-trail-north-carolina/9917494497

Erzsebet Frey (Eli Frey) is an ecologist and online entrepreneur with a Master of Science in Ecology from the University of Belgrade. Originally from Serbia, she has lived in Sri Lanka since 2017. Eli has worked internationally in countries like Oman, Brazil, Germany, and Sri Lanka. In 2018, she expanded into SEO and blogging, completing courses from UC Davis and Edinburgh. Eli has founded multiple websites focused on biology, ecology, environmental science, sustainable and simple living, and outdoor activities. She enjoys creating nature and simple living videos on YouTube and participates in speleology, diving, and hiking.

🌿 Explore the Wild Side!

Discover eBooks, guides, templates and stylish wildlife-themed T-shirts, notebooks, scrunchies, bandanas, and tote bags. Perfect for nature lovers and wildlife enthusiasts!

Visit My Shop →