Trophic levels represent the sequential steps through which energy flows in an ecosystem, from producers like grasses and phytoplankton that capture sunlight, to herbivores that consume them, and finally to predators at higher positions. Each transfer retains only about 10% of the available energy, which explains why ecosystems support fewer top predators than plant-eaters. These feeding relationships reveal how communities maintain balance and respond to disturbances, with examples ranging from African savannas to ocean food webs demonstrating the principle’s universal application across environments.

Definition

A trophic level, which comes from the Greek word “trophe” meaning nourishment, represents a step in the sequential flow of energy through an ecosystem—the community of living organisms and their physical environment.

Each level in this trophic hierarchy contains organisms that share the same function in the food chain, whether they’re producers creating energy from sunlight or consumers obtaining energy by eating other organisms.

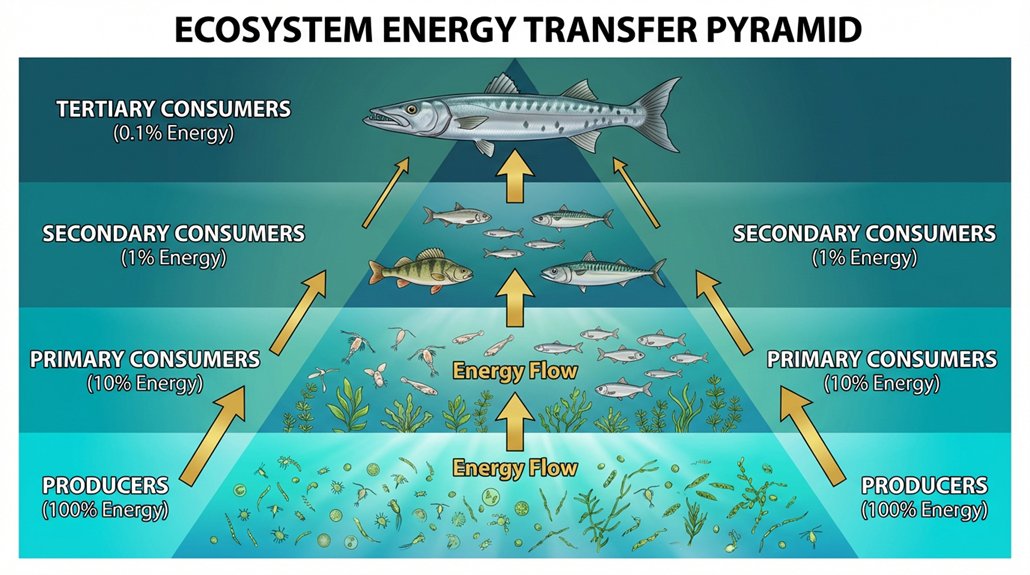

The structure resembles an energy pyramid, with producers forming the broad base and successive consumer levels stacking above, each one smaller than the last because energy diminishes as it transfers upward.

This pyramid shape reflects a fundamental ecological principle: only about ten percent of energy passes from one trophic level to the next, while the rest dissipates as heat or fuels the organisms’ life processes.

Understanding these levels helps us recognize how energy moves through nature’s interconnected web.

Ecological significance

Trophic levels serve as organizing principles that reveal how ecosystems maintain their stability and why certain environments can support more life than others. Understanding these hierarchical feeding positions allows ecologists to predict how disturbances—such as the removal of a predator or the introduction of a new species—will ripple through an entire community.

Trophic dynamics, which describe the movement and transformation of energy as it passes from one level to the next, help explain why ecosystems function as they do. Energy transfer between levels typically converts only about ten percent of available energy into biomass, meaning each successive level supports fewer organisms. This inefficiency shapes everything from population sizes to food web complexity.

When scientists examine trophic structures, they’re fundamentally reading a blueprint that shows how nutrients cycle, which species depend on one another, and where interventions might restore balance in degraded habitats.

Real World Examples

Examining specific ecosystems reveals how trophic levels—the hierarchical feeding positions organisms occupy in a food chain—function in nature’s diverse settings.

The African savanna demonstrates a classic terrestrial system where grasses support herbivores like zebras and wildebeests, which in turn sustain large predators such as lions and cheetahs.

Marine environments and temperate forests present equally compelling patterns of energy transfer, though each ecosystem’s unique conditions shape the particular species that fill these fundamental ecological roles.

African Savanna Food Chain

Spanning vast stretches of East Africa, the savanna ecosystem demonstrates trophic levels through interactions that have shaped life there for millions of years.

Grasses occupy the producer level, converting sunlight into energy through photosynthesis—the process by which plants create food from light.

Herbivore interactions define the second trophic level, where zebras, wildebeests, and gazelles consume these grasses, transferring energy upward through the food chain.

Predator dynamics emerge at the third level: lions, cheetahs, and hyenas hunt these plant-eaters, receiving only about 10% of the energy stored in their prey’s bodies.

Vultures and decomposers complete the cycle, breaking down remains and returning nutrients to the soil, where grasses absorb them once again to sustain this ancient, interconnected system.

Marine Ecosystem Trophic Structure

Beneath the ocean’s surface, where sunlight filters through water in diminishing bands of blue and green, marine ecosystems organize themselves into trophic levels that mirror terrestrial patterns yet follow their own distinct rules.

Phytoplankton—microscopic floating plants—capture solar energy as primary producers, forming the foundation that supports all marine life above them. Small zooplankton graze on these photosynthetic organisms, becoming prey for juvenile fish and filter feeders.

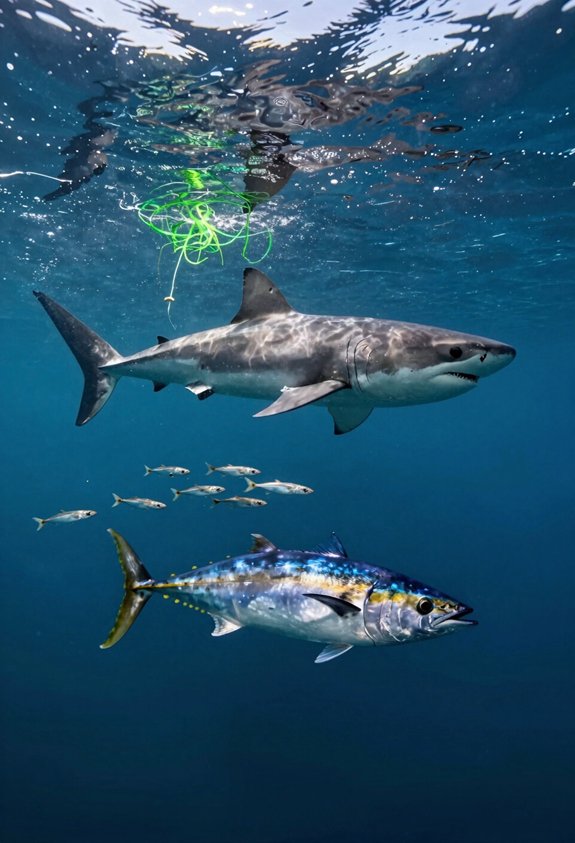

Energy transfer occurs as larger predatory fish consume smaller ones, with each level losing approximately ninety percent of available energy to metabolic processes and heat. Apex predators like sharks and orcas occupy the highest trophic positions, regulating predator prey dynamics throughout the water column.

These interconnected feeding relationships maintain balance within ocean communities, demonstrating how energy flows from sunlight to top consumers.

Temperate Forest Energy Flow

While ocean ecosystems stretch across vast expanses where currents carry nutrients and organisms drift with the tides, temperate forests root their energy networks in soil and seasonal rhythms, creating trophic structures that remain anchored to specific geographic locations year after year.

In these woodland communities, energy transfer begins with oak trees, maples, and understory plants converting sunlight into forest biomass—the total mass of living material within the ecosystem.

Primary consumers such as deer, caterpillars, and squirrels feed on leaves, nuts, and bark, while secondary consumers including foxes, owls, and shrikes hunt these herbivores.

Decomposers like fungi and bacteria recycle nutrients from fallen logs and leaf litter, completing the cycle and returning essential elements to the soil where producers can access them again.

Related concepts

Trophic levels don’t exist in isolation—they’re part of a broader framework of ecological concepts that help scientists understand how energy and matter move through living systems.

Trophic dynamics, which refers to the study of how energy transfers between different feeding levels, reveals patterns that extend beyond simple food chains. Energy pyramids visualize these transfers by showing how available energy decreases at each successive level—a graphical representation that makes the 10% rule immediately apparent to anyone examining it.

These concepts connect closely with nutrient cycling, the process by which essential elements like nitrogen and carbon move through ecosystems and return to the soil.

Understanding biomass, the total mass of living organisms at each level, also helps ecologists predict how changes in one population might cascade through an entire community, affecting everything from primary producers to apex predators in measurable ways.

If you want to strengthen your ecology foundation, start with the Ecology Basics to understand core concepts step by step. Dive deeper with 25 Key Concepts in Ecology with Real-World Examples to see how theory applies in nature. If you prefer to learn ecology fast and simply, the Ecology Flashcards are perfect for quick, focused learning. For a complete reference, explore the Glossary of Ecology Terms with 1,500+ terms explained in simple language, available as a PDF for use on any device.

🌿 Explore the Wild Side!

Discover eBooks, guides, templates and stylish wildlife-themed T-shirts, notebooks, scrunchies, bandanas, and tote bags. Perfect for nature lovers and wildlife enthusiasts!

Visit My Shop →