Abiotic factors—the non-living components of ecosystems such as sunlight, temperature, water availability, and soil composition—shape which organisms can survive in any given environment and how they’ll adapt to meet those conditions. These physical and chemical elements operate independently of life yet profoundly influence species distribution, establishing metabolic boundaries through temperature gradients and dictating plant communities through nutrient availability. Desert cacti withstand extreme heat and scarce rainfall, while mountain elevations create distinct biological zones where species develop specialized adaptations like thicker fur or enhanced oxygen capacity, demonstrating how abiotic conditions filter life forms across landscapes and altitudes alike.

Definition

When ecologists study the living world, they recognize that organisms don’t exist in isolation—they’re shaped by both other living things and by the non-living elements surrounding them.

Abiotic factors refer to these non-living components of an ecosystem—the physical and chemical elements that influence where organisms can survive and how they function. These environmental influences include sunlight, temperature, water availability, soil composition, air currents, and mineral nutrients.

Unlike biotic factors, which involve interactions between living organisms like predation or competition, abiotic components operate independently of life itself, though they profoundly affect it. A desert plant, for instance, must adapt to intense heat and scarce water: both abiotic conditions that determine whether it thrives or perishes.

Understanding these non-living forces helps ecologists predict species distribution, explain population changes, and recognize why certain habitats support specific communities while excluding others.

Abiotic factors form the stage upon which all ecological dramas unfold.

Ecological significance

Although abiotic factors might seem like mere background conditions, they actually serve as primary architects of ecological structure, determining which species can inhabit a region and shaping the intricate relationships that develop among those organisms.

Temperature gradients establish metabolic boundaries—organisms simply can’t survive where conditions exceed their physiological tolerance ranges. Nutrient availability in soil and water dictates plant distribution, which then determines where herbivores can thrive, creating cascading effects throughout food webs.

Light penetration through forest canopies or water columns controls photosynthetic activity, fundamentally influencing energy flow in ecosystems. Precipitation patterns govern whether forests, grasslands, or deserts develop in particular locations.

These abiotic elements work together, interacting in complex ways: warmer temperatures accelerate decomposition, which affects nutrient cycling, while humidity influences both temperature regulation and water availability.

Understanding these factors helps ecologists predict how communities respond to environmental changes, whether natural or human-caused.

Real World Examples

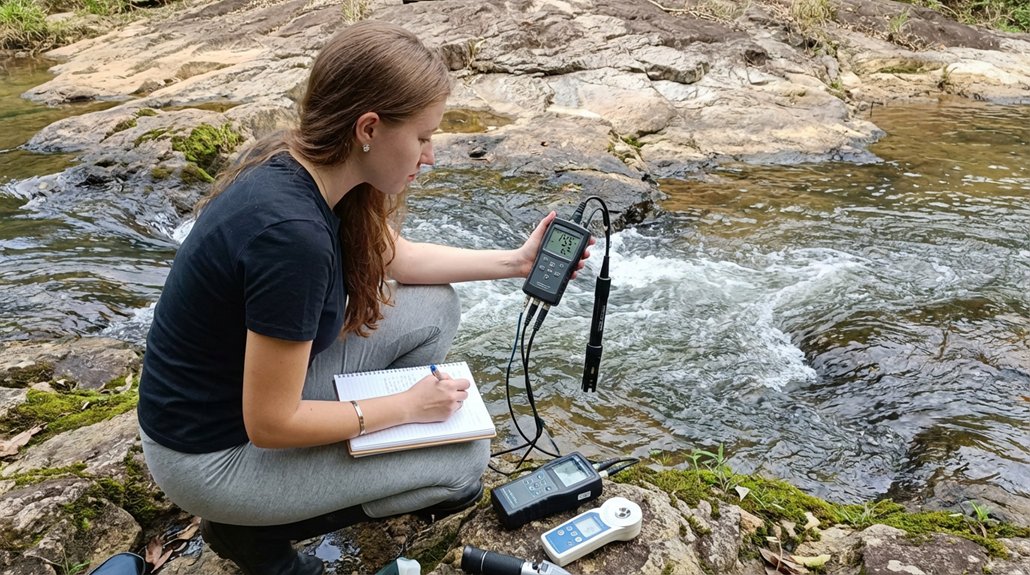

Observing abiotic factors—those non-living physical and chemical components of an ecosystem—in actual environments reveals how powerfully they shape the distribution and survival of organisms.

The scorching temperatures and minimal rainfall of deserts create conditions that only specially adapted species can endure, while the salinity levels in ocean waters determine which marine organisms can maintain the proper balance of salt and water in their cells.

Similarly, as one climbs a mountain, the changing elevation brings shifts in temperature, oxygen availability, and atmospheric pressure, creating distinct biological zones where different communities of plants and animals thrive at different heights.

Desert Temperature and Rainfall

The Sahara Desert illustrates how extreme temperature fluctuations and minimal rainfall shape an ecosystem’s character, offering a clear window into the way abiotic factors—the non-living components of an environment—determine which organisms can survive in a given place.

Temperature extremes define daily life here: daytime readings soar above 120°F, while nights plunge toward freezing, creating conditions that only specially adapted species can endure. Rainfall variability compounds these challenges, with annual precipitation averaging less than three inches and arriving unpredictably across years.

Plants like cacti store water in thick tissues, while animals such as fennec foxes hunt nocturnally to avoid heat stress. These adaptations emerge directly from the desert’s harsh abiotic conditions, demonstrating how non-living factors filter which life forms persist.

Ocean Salinity Affecting Life

When seawater’s salt concentration shifts even slightly, it acts as a powerful filter that determines which marine organisms can inhabit particular ocean zones—a reality vividly illustrated in places where freshwater rivers meet the sea.

Estuaries, where rivers discharge into oceans, create brackish environments with fluctuating salt levels that challenge most species. Only organisms with exceptional salinity tolerance—the ability to withstand varying concentrations of dissolved salts—can thrive in these changing waters.

Oysters, barnacles, and certain crabs possess specialized cellular mechanisms that regulate internal salt balance, allowing them to survive where others cannot.

This selective pressure shapes marine biodiversity patterns across coastlines: areas with stable salinity support vastly different communities than zones experiencing constant fluctuation, demonstrating how a single abiotic factor profoundly influences which life forms colonize specific marine habitats.

Mountain Elevation Impact Zones

Just as salinity creates invisible boundaries in horizontal ocean zones, elevation establishes distinct vertical life zones on mountainsides—bands of different climates stacked atop one another like layers in a cake, each supporting communities adapted to specific temperature ranges, moisture levels, and atmospheric pressures.

Mount Kilimanjaro demonstrates these biodiversity gradients beautifully: tropical forests thrive at its base, temperate moorlands occupy middle elevations, and alpine deserts exist near its summit where few organisms survive.

Scientists observe that temperature drops approximately 6.5°C per kilometer of altitude gained, creating altitude adaptation challenges that favor species with specialized traits—thicker fur in mountain goats, reduced water loss mechanisms in high-elevation plants, and enhanced oxygen-carrying capacity in blood cells.

These elevation zones prove that vertical distance matters as much as horizontal distance in shaping ecological communities.

Related concepts

Understanding abiotic factors becomes richer when one considers how they connect to several broader ecological principles, each of which illuminates a different aspect of how non-living elements shape life on Earth.

Carrying capacity—the maximum population size an environment can sustain—depends heavily on abiotic resources like water availability and soil composition, which determine how many organisms can survive in a given space.

Limiting factors, those environmental conditions that restrict population growth, often stem from abiotic sources: insufficient light availability in dense forests, for instance, prevents certain plant species from thriving beneath the canopy.

Environmental gradients, the gradual changes in conditions across landscapes, create zones where different communities flourish based on tolerance ranges for temperature, moisture, and other non-living variables.

Ecological succession, the process by which communities change over time, begins with pioneer species that can tolerate harsh abiotic conditions—bare rock, intense sunlight, minimal nutrients—and gradually transforms the physical environment itself.

If you want to strengthen your ecology foundation, start with the Ecology Basics to understand core concepts step by step. Dive deeper with 25 Key Concepts in Ecology with Real-World Examples to see how theory applies in nature. If you prefer to learn ecology fast and simply, the Ecology Flashcards are perfect for quick, focused learning. For a complete reference, explore the Glossary of Ecology Terms with 1,500+ terms explained in simple language, available as a PDF for use on any device.

🌿 Explore the Wild Side!

Discover eBooks, guides, templates and stylish wildlife-themed T-shirts, notebooks, scrunchies, bandanas, and tote bags. Perfect for nature lovers and wildlife enthusiasts!

Visit My Shop →